Dear Diary,

This was a dramatic week around here, following the public announcement of the independent bookstore I am starting in downtown Evanston, Bookends & Beginnings. Mr. Darcy is quite excited, not just because he will be curating several of the store’s subject-areas, but because he thinks it is likely to divert my personal cookbook acquisitions program in a potentially more remunerative direction. From time to time he looks hopefully at the packed shelves in our home where books with titles like Cold Spaghetti at Midnight, Imperial Mongolian Cooking, and Feasting & Fasting in Crete all peacefully coexist, and says, “Have you given any thought to selling any of these in the store, dear?”

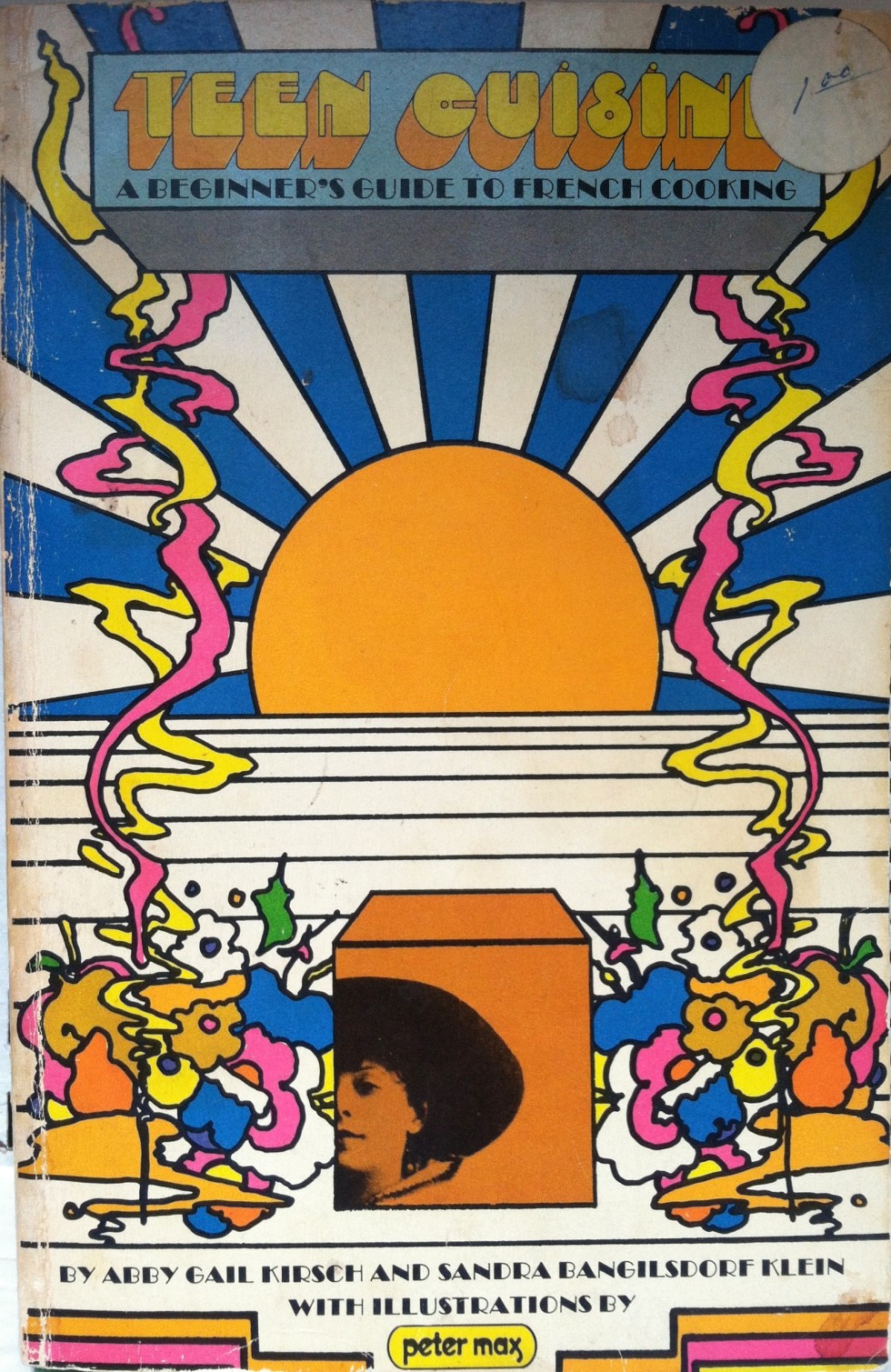

That’s just crazy talk, of course. I wouldn’t dream of selling any of my own personal cookbooks in the bookstore. Like any  kind of personal book collection, they bear witness to a long passion, and to the path I traveled to arrive in the mental space I inhabit today, beginning with my first two great serious culinary achievements at the age of 13: a perfect cheese soufflé based on the instructions in Teen Cuisine by Abby Gail Kirsch and Sandra Bangilsdorf Klein (with psychedelic illustrations by Peter Max, circa 1969) and an impeccable Linzer Torte made from the Time-Life volume on The Cooking of Vienna’s Empire. There’s a recipe for the exact Portuguese Sweet Bread my family used to buy from the Scottish Bakehouse on Martha’s Vineyard in the 1970s, which I can replicate at any time because I own The Scottish Bakehouse Cookbook; the red/orange-stained recipe for Chicken Paprika from the Joy of Cooking, which became a staple of my newlywed kitchen in the days of my first marriage; and the recipe for an amazingly spiced Shrimp in Coconut Milk from Savoring the Spice Coast of India that my grown-up sons still ask me to make whenever they’re coming home.

kind of personal book collection, they bear witness to a long passion, and to the path I traveled to arrive in the mental space I inhabit today, beginning with my first two great serious culinary achievements at the age of 13: a perfect cheese soufflé based on the instructions in Teen Cuisine by Abby Gail Kirsch and Sandra Bangilsdorf Klein (with psychedelic illustrations by Peter Max, circa 1969) and an impeccable Linzer Torte made from the Time-Life volume on The Cooking of Vienna’s Empire. There’s a recipe for the exact Portuguese Sweet Bread my family used to buy from the Scottish Bakehouse on Martha’s Vineyard in the 1970s, which I can replicate at any time because I own The Scottish Bakehouse Cookbook; the red/orange-stained recipe for Chicken Paprika from the Joy of Cooking, which became a staple of my newlywed kitchen in the days of my first marriage; and the recipe for an amazingly spiced Shrimp in Coconut Milk from Savoring the Spice Coast of India that my grown-up sons still ask me to make whenever they’re coming home.

I’ve heard people say that cookbooks are going the way of other print books: giving way to content found more conveniently online. Faced with an uninspiring package of chicken thighs, many people nowadays just Google “chicken thighs” and come up with a recipe of uncertain origins they’ll decide to trust according to how many stars its anonymous reviewers have assigned it. I’ve done that too, occasionally, but to me the convenience of being able to Google your pressing dinner dilemma has nothing whatsoever to do with the critical role of cookbooks in my life.

The point of a cookbook–as with any book, really–is the relationship you develop with its particular author. Anything Claudia Roden tells me about Middle Eastern cooking I implicitly trust, because unlike a long string of anonymous online critics, I’ve come to know her through the stories she uses food to tell, as well as the food I’ve made according to her directions. I have my issues with Martha Stewart’s persona, but when I’m entertaining I know that even something I’ve never tried making from one of her cookbooks is likely to come out exactly right.

Last week I was invited by the Chicago Humanities Festival to talk to a group of their supporters about the significance of Alice Waters in today’s culinary landscape. Alice was making an appearance that evening along with Ruth Reichl before a sold-out Humanities Festival audience, and my talk was intended as a sort of amuse bouche. I decided to dramatize some of Alice’s most fundamental principles by revisiting a few recipes for the kind of food we were all eating in the 1960s and 70s, using a cookbook I had recently acquired for the new bookstore. It’s one of those classic spiral-bound, self-published church cookbooks, compiled by the Mother’s Circle of the Cross and Crown Lutheran Church in 1976, which would have been Alice’s early days at Chez Panisse. The church cookbook features one particularly hideous recipe for a “Cheese Topped Gelatin Salad” containing all of the following ingredients: lemon gelatin, miniature marshmallows, crushed pineapple, bananas, prepared whipped topping, and grated cheese. Really? This was referred to as salad? Meanwhile, there was Alice, smuggling seeds for heirloom lettuces home from her trips to France so she could recreate the mixed-leaf salads she had enjoyed there, an innovation that eventually spread across the country as the mesclun salad we can all (ironically) buy in pre packed vacuum-sealed supermarket bags today.

There was a recipe for “Chipper Tuna Casserole” involving a can of mushroom soup, a can of tuna, a can of peas, and a bag of potato chips–nothing, mind you, that couldn’t have been lying around in your nuclear bomb shelter for the past decade (assuming you have a sense of willpower around potato chips). Meanwhile, there was Alice out in Berkeley, inventing the mantra “fresh, local, seasonal” that we are still just growing into as a country today.

Then there was a recipe for “Meat Balls,” consisting of nothing but ground beef, crumbs, onion, and garlic salt. The instructions evoked some taciturn Nebraska farm wife going about her business with a minimum of mental fuss: “Make balls – brown. Add 7 oz. catsup and 8 oz. tomato sauce. Serve over broad noodles.”

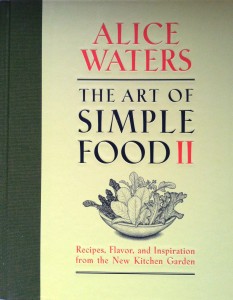

In contrast, I picked up Alice’s newest cookbook The Art of Simple Food II and read aloud her recipe for Lovage Meatballs. Lovage, in case you’ve never encountered it, is a parsley-like herb with “a sweet celery flavor that adds a perfect note to meat, especially ground meat.” Alice is aware that you probably don’t have any in your spice rack, and that you can’t even run out and buy some in a McCormick spice container; in this book she’s moved beyond nudging you toward relying always on your local farmer’s market. She wants you to grow your own, and the recipe actually begins with growing tips, so plan ahead. The actual recipe calls for ground pork and chicken (no beef), red wine, garlic, and chile flakes, besides the lovage and a few other things, so you can see we’re going to get some subtlety of flavor, and her instructions include the admonition to “mix gently, using stiff open fingers like a comb,” an unusually sensual, literary description of the proper technique for kneading meatball mix, in my opinion.

In contrast, I picked up Alice’s newest cookbook The Art of Simple Food II and read aloud her recipe for Lovage Meatballs. Lovage, in case you’ve never encountered it, is a parsley-like herb with “a sweet celery flavor that adds a perfect note to meat, especially ground meat.” Alice is aware that you probably don’t have any in your spice rack, and that you can’t even run out and buy some in a McCormick spice container; in this book she’s moved beyond nudging you toward relying always on your local farmer’s market. She wants you to grow your own, and the recipe actually begins with growing tips, so plan ahead. The actual recipe calls for ground pork and chicken (no beef), red wine, garlic, and chile flakes, besides the lovage and a few other things, so you can see we’re going to get some subtlety of flavor, and her instructions include the admonition to “mix gently, using stiff open fingers like a comb,” an unusually sensual, literary description of the proper technique for kneading meatball mix, in my opinion.

Although I’ve never met Alice Waters personally, as I watched her from the audience later that evening, at the Humanities Festival event, I was thinking: Yes, she’s just exactly what I would have expected, based on her cookbook. A soft-spoken subversive swathed in a sensual silk scarf, expressing a series of revolutionary ideas in the most matter-of-fact, utterly beguiling way.

I didn’t actually meet her that evening, but then this afternoon, I opened a package from the Humanities Festival that came in the mail to find a copy of her cookbook, autographed to me. I’m probably more thrilled than if I’d had a few seconds to try to connect with Alice Waters, Celebrity on a Book Tour. Because this way–through her cookbook–she’s come to take up permanent residence in my home, and we’ll be able to start developing a relationship I expect is going to last a lifetime.