Dear Diary,

A few weeks ago a British colleague poked his head into my office and said, “You’re quite interested in cooking subjects, aren’t you?” (My day job has nothing whatsoever to do with cooking; I’m not even the one in the office who brings in little home-made treats in Tupperware to share.)

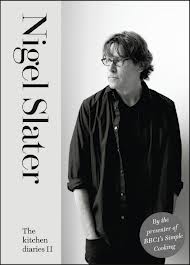

The colleague said he had ended up with a duplicate copy of a cookbook and was seeking a good home for it. It was by British cooking personality Nigel Slater, with whom I was unacquainted, since my knowledge of TV cooking personalities is limited to those whose shows happen to air during the exceedingly limited stints when I happen to be on the elliptical trainer at the gym. Slater’s book appealed to me immediately, since it’s in the form of a kitchen diary. On the cover, Nigel looks  unpretentious and a little rumpled in his un-ironed shirt, glancing toward the offstage right with a slight look of irritation as though he hopes the photo shoot will be over soon, and the book’s flap copy, which on an American book would boast shamelessly about his celebrity prowess, simply features a recipe for Pistachio and Lemon Cookies. The diary entries follow the calendar year, describing the dishes he’s making, with commentary like, “It wasn’t, on reflection, the wisest of days to make marmalade,” and, “There is a small bundle of asparagus in the fridge. It is not enough for two, and whilst a plate of asparagus can be eaten as a lone, sybaritic feast, I am going to stretch my bounty so it will feed two.” In short, Slater comes across not as a Lifestyle Bully or a Culinary Prosyletizer or an Ethnic Cuisine Chamber of Commerce, but as the guy in the thatched cottage down the road who’s invited you over for the thing he’s throwing together out of what he picked up at the farmer’s market this morning and the herbs in his kitchen garden.

unpretentious and a little rumpled in his un-ironed shirt, glancing toward the offstage right with a slight look of irritation as though he hopes the photo shoot will be over soon, and the book’s flap copy, which on an American book would boast shamelessly about his celebrity prowess, simply features a recipe for Pistachio and Lemon Cookies. The diary entries follow the calendar year, describing the dishes he’s making, with commentary like, “It wasn’t, on reflection, the wisest of days to make marmalade,” and, “There is a small bundle of asparagus in the fridge. It is not enough for two, and whilst a plate of asparagus can be eaten as a lone, sybaritic feast, I am going to stretch my bounty so it will feed two.” In short, Slater comes across not as a Lifestyle Bully or a Culinary Prosyletizer or an Ethnic Cuisine Chamber of Commerce, but as the guy in the thatched cottage down the road who’s invited you over for the thing he’s throwing together out of what he picked up at the farmer’s market this morning and the herbs in his kitchen garden.

My colleague said he and his wife were great fans of Slater’s and had his whole series of cookbooks, and to me it’s one of life’s great pleasures to be given a cookbook that someone else swears by, or one that you wouldn’t otherwise have discovered. I decided to thank him by proposing a dinner party at which we would all cook a Slater dish, with me bringing the entree.

Which is how yesterday–on a beautiful late-spring day when the air was scented with lilacs–I came to be making an Aubergine, Thyme, and Feta Tart. So right there you see that one of the challenges of cooking from an English cookbook not re-edited for the North American market is the slight language barrier, in which “eggplants” are “aubergines,” ounces are grams, inches are centimeters, and you might find such  mystifying instuctions as, “Slice the remaining aubergine into rounds approximately the thickness of a two-pound coin.”

mystifying instuctions as, “Slice the remaining aubergine into rounds approximately the thickness of a two-pound coin.”

The recipe appeared charmingly simple, calling only for three eggplants, two cloves of garlic, half a pound of feta cheese, and 10 sprigs of thyme, utilizing prepared (i.e. frozen) puff pastry for the crust. (I’m leaving out the things you’d just have lying around anyway, like olive oil, salt, pepper, and an egg to make an egg-wash for the crust.) But from a “Fear of Frying” point of view, even that list includes a few red flags, notably the puff pastry which can be fussy to work with even when you buy it ready-made, and the eggplants, which most cookbook authors will suggest putting through a whole preliminary process of salting and draining that supposedly diminishes their bitterness and their capacity to simply suck up entire containers of olive oil when you fry them.

One thing I’m going to tell you about Nigel, now that I’ve cooked with him, is that if you’re the Cook’s Illustrated type–who prefers pages and pages of diagrams and blow-by-blow instructions and an entire brigade of kitchen Ph.D.s scientifically testing each recipe to make sure that the recipes are papally infallible–he’s not your guy. He doesn’t bother with the whole salting procedure, for instance, since he believes bitterness has been bred out of commercially available eggplants, and so what if the slices soak up entire containers of olive oil: ‘It renders the texture soft and silky and has an affinity with the flesh that is both ancient and magical. It is my belief that without olive oil, an aubergine has little to say.”

I happen to agree with Nigel on this. I’d guess it was probably his more conservative editors who decided to officially claim the quantity of olive oil required to fry an entire eggplant–sliced to the width of two-pound coins–is 4-5 tablespoons, when in fact I’d guess I needed closer to half a cup (and even then, I’m going to say, any self-respecting Greek housewife would have used twice as much again).

It wasn’t Nigel’s fault that I over-defrosted the puff-pastry crust, letting it go to full room temperature on the kitchen counter, so that by the time I attempted to unfold it it had all glommed together into one solid lump. This is one of those moments when I think a truly Fe arful Fryer would have thrown the whole project out the window, mixed a gin and tonic, and resolved to pick up a take-out entree on the way over to dinner. but I thought of Julia’s mantra: “If you’re alone in the kitchen, who’s to know?” I just rolled out the large lump to roughly the required width, smashing all the folds into one another rather than unfolding them, because after all, puff pastry is all about layers and a few more shouldn’t really hurt it. The photograph of the finished dish was reassuringly rustic–a word I love because it takes our fallibilities and the fallibilities of our food and makes them charming.

arful Fryer would have thrown the whole project out the window, mixed a gin and tonic, and resolved to pick up a take-out entree on the way over to dinner. but I thought of Julia’s mantra: “If you’re alone in the kitchen, who’s to know?” I just rolled out the large lump to roughly the required width, smashing all the folds into one another rather than unfolding them, because after all, puff pastry is all about layers and a few more shouldn’t really hurt it. The photograph of the finished dish was reassuringly rustic–a word I love because it takes our fallibilities and the fallibilities of our food and makes them charming.

And then came that moment, familiar to every cookbook afficionado, when you look at an instruction in a recipe, knowing in your heart of hearts that it’s wrong, and feel that little twinge of panic because you are expected to arrive at someone’s house with the beautiful finished dish in an hour and and a half and you have to make a call about whether to trust the instructions or your own instincts. Is it possible to roast a whole eggplant till the flesh is tender in only 25 minutes in a home oven? Not in my experience. Am I wrong in thinking a 180 degree Celsius oven is actually more or less our 350 degree Fahrenheit oven, because that’s what the online conversion website suggests. Maybe it’s the temperature and not the time that’s wrong (the clock is ticking down, we have to leave soon!) and I should crank the oven up to 400 or 450! Maybe then the eggplant will spontaneously combust and that’s how it will attain the ”smoky” flavor Nigel alludes to, which I can’t otherwise account for.

No, I should trust Nigel! He looks so down-to-earth and trustworthy on the cover, I can’t believe he doesn’t know something about eggplant-roasting that I don’t know. But when, after 25 minutes, I poke at the eggplants with the back of a spoon and the flesh barely gives, I give them an additional 20 minutes, then try stripping off the skin and mashing the pulp with a fork, as directed. This is supposed to produce an “aubergine cream” but in fact much of the flesh is still lumpy and unyielding.

This, Diary, is why God invented the microwave. Ten minutes on High later I have something roughly resembling the “cream” Nigel alludes to. As swiftly as I can, I spread it on my rustic puff-pastry crust, which has miraculously puffed exactly as it was supposed to (and was made visually striking by a small trick of brushing just the outside border with the egg-wash). Then I top it with the slices of fried eggplant, seasoned with salt, pepper, and thyme; crumble feta cheese over the top; and pop it into the oven for roughly the time it takes to run upstairs and make myself presentable for dinner.

The finished tart emerges from the oven in the nick of time, looking spectacular–perhaps even more alluring than the picture in Nigel’s book. We discove r later in the evening, sharing it with my colleague and his wife, that treated in this simple manner (with enough olive oil) the eggplant does, in fact, have something important to say. The process might have been slightly harrowing–like, for instance, driving on the left side of the road–but that’s the way things can get sometimes when you are cooking in a familiar but still somehow foreign language.

r later in the evening, sharing it with my colleague and his wife, that treated in this simple manner (with enough olive oil) the eggplant does, in fact, have something important to say. The process might have been slightly harrowing–like, for instance, driving on the left side of the road–but that’s the way things can get sometimes when you are cooking in a familiar but still somehow foreign language.